I wrote a lot of about Scottie Reynolds during his high school basketball career. As one of the top recruits in the nation -- one that had to go through the recruiting process twice after opting out of his scholarship with Oklahoma and signing with Villanova when coach Kelvin Sampson left for Indianna -- Reynolds is the type of athlete/person that makes guys like me want to do this job. If you don't know the name "Scottie Reynolds" by now, you will soon.

I wrote a lot of about Scottie Reynolds during his high school basketball career. As one of the top recruits in the nation -- one that had to go through the recruiting process twice after opting out of his scholarship with Oklahoma and signing with Villanova when coach Kelvin Sampson left for Indianna -- Reynolds is the type of athlete/person that makes guys like me want to do this job. If you don't know the name "Scottie Reynolds" by now, you will soon.

Scottie Reynolds: God, Family, and Basketball

Hoops Handbook 2005-2006

BJ Koubaroulis

Additional reporting by Jeff Graham, Greg Wyshynski, and Rich Sanders

Dec. 6, 2005

He walks simply and expressionless, his eyes locked straight forward. It may be old habit for Scottie Reynolds; a behavior he likely picked up when he lived in Chicago. Maybe it's because he knows he's being watched. Wherever he goes, on the court or off the court, the Herndon senior guard commands attention.

Watch close enough, and his step shows a small kick — the walk of someone who carries both the pressures of star status on one shoulder and a major chip on the other.

The path he's walked is ground tread before only by the greats that have graced the musty gymnasiums and old hardwood floors of the Northern Region.

But his step, his game, his path might lead to being the best ever.

The comparisons are obvious and deliberate. Reynolds — the Northern Region player of the Year for the past two seasons — has catapulted himself into regional lore. Much like former South Lakes star and NBA All-Star Grant Hill, who averaged 27 points per game his senior year. Reynolds averaged 32.7 points per game last season — as a junior.

"Grant and those guys couldn't do that. No one around here has averaged points like that," said West Potomac coach David Houston, who played point guard for West Springfield during the late 1980's and early 1990's — the Grant Hill era.

Reynolds perks up when Hill is mentioned. The two have never met in person, though they share the same barber. Reynolds has heard, through their mutual friend with the sheers, that Hill might make an appearance at the Dec. 9 rivalry game between their two alma maters.

"We'll see if they can beat South Lakes this year," said Hill of the rivalry game, which has a history Reynolds has studied intensely and claims to know very well.

As he creates new entries in the regional record book, Reynolds is quickly becoming his own chapter in its history book — joining names like Hill, Dennis Scott, Tommy Amaker and Hubert Davis, the former Lake Braddock star that went on to pro success with the New York Knicks and is currently an analyst with ESPN.

"First of all, to be compared with those guys is an honor in itself," said Reynolds.

Lake Braddock boys basketball coach Brian Metress has no doubts that Reynolds belongs in that company.

"I see nothing wrong with [Scottie]," said Metress. "I think he's the best player in Northern Virginia since I've been coaching, and that includes Hubert and Grant. He's more dominant. They had personalities that deferred to other teammates; Scottie just comes out and just crushes you."

In his 15th season at Chantilly, head coach Jim Smith remembers what it was like to coach against Hill.

"Grant would score 18, 20 points, but could hurt you in 10 different ways," said Smith. "You can do whatever you want against [Scottie] ... he can still score 40 on you."

No matter if their opinions differ, or whom they chose as the greatest, each coach has one thing in common — a story about how they were amazed by Reynolds.

"I know he's better than our level," added Metress.

It's a level that only Hill could understand.

"I didn't feel any pressure at all. We were pretty talented," recalled Hill, a 1989 graduate of South Lakes and 6-foot 8-inch All-American that went on to star at Duke University.

"I didn't feel any pressure until college."

THE PRESSURES AND COMPARISONS are nothing new for Reynolds. Like when South Lakes head coach Wendell Byrd, who coached Hill, admits the two have contrasting styles of play.

THE PRESSURES AND COMPARISONS are nothing new for Reynolds. Like when South Lakes head coach Wendell Byrd, who coached Hill, admits the two have contrasting styles of play."Scottie's [shooting] range is much further than Grant's was," said Byrd. "Off the dribble there was no one that could handle Grant. Grant's game was defensive and offensive. Scottie is known for his offensive thrust."

Madison head coach Chris Kuhblank, who played against Davis while at Lee in the late 1980's, added that Davis might have been at a disadvantage.

"The 3-point line didn't come out until his senior year," said Kuhblank.

Reynolds welcomes the comparisons and criticisms. "Basically, I let people say what they want to say and I go about my business. If somebody says Scottie doesn't do this or Scottie doesn't do that, okay," said Reynolds.

But as much as the 18-year old has trained himself to ignore the criticism, it is the criticism which fuels his success. He does care what "they" say, and he's better for it.

Reynolds sits back in his bedroom after long days and nights at practice, cracking a smile when he looks at a certain wall.

"I reminisce on what I've accomplished," he said.

Like the time he set Herndon's high-scoring record with a 53-point performance last season in a 91-81 win over I.C. Norcom, just a day after setting his career high at 46 points in an 83-53 win over Oakton. Both records were his to break. The previous Herndon High School record was 43 points — Scottie's record.

His bedroom wall isn't clad with posters like that of a normal teenager — but Reynolds is beyond believing that his life ever was, or ever will be, normal.

"I have a whole wall of all the negative things people have said since my freshman year," he said of the estimated 25 sheets of paper he's tacked up to his wall.

Select quotes from message boards, chat rooms, Web sites, and news articles are his decoration.

Each is a clipping he gets from his coaches. Each is a reminder. Each is fuel.

"Whatever I can do to prove people wrong, I'm going to try to do it because I've been doing it my whole life," said Reynolds.

LIKE WHEN he turned down several offers to play in private schools, and he was told "You're not going to make it in soft Northern Virginia," Reynolds recalled. The answer to why Reynolds turned down those offers is much like his walk — simple.

"To prove them wrong," he said with a smile. "I like proving people wrong so that I can walk out of the gym just cocking my smile."

Herndon head coach Gary Hall added that all Northern Region coaches owe Reynolds a "debt of gratitude" for showing loyalty to Northern Virginia and for boosting the area's prestige by staying in the public school system.

"Now every coach can point to Scottie Reynolds and say 'look,'" said Hall, of keeping young basketball talents in the public school system.

Hall, in his 17th year at Herndon, was an assistant to Byrd during the Hill era.

"I forget how special Grant was sometimes," Hall says when he claims that Scottie is the better of the two. "People don't realize the things [Grant] went through. It's not easy being a superstar. The way that he handled it, the pressure comes from within. The same thing you see with Scottie."

But as much as Hill and Reynolds are compared and contrasted, one thing Hall and Byrd both agree on is that it is a strong family core that has kept both on the path to success.

"Both families handled everything in such as classy manner," said Hall, who can remember sitting in Hill's living room and watching Div. 1 basketball with Grant's father, Calvin.

"There was never any horror stories. A few. But it never got to a point where it was so chaotic with the recruiting. You didn't hear about street agents and leaches," added Hall, regarding Reynolds's days as a recruit.

REYNOLDS IS PART of a racially mixed set of children to a pair of white parents.

"So we are all like, you know, like an Oreo," he says while he twists his fingers as if he's opening the famous cookie.

"I was adopted right when my momma had me," he said. "My foster parents were my parents that I have now. I've been with them since the beginning. My [adopted] mom had three [children], they are white and she adopted three of us [that are black]. Me, my, younger brother and my younger sister."

For Reynolds, only one thing comes before his family — God.

"God's first in my life, first and foremost," said Reynolds. "Then it's my family. And then there's basketball."

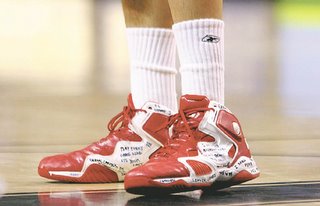

While it has become commonplace for athletes and coaches alike to show reverence toward a higher power, Reynolds — who won't specify a religion and says he follows the New Testament as a Christian — has gone above and beyond the call to stay true to his religion.

"I've missed games for it," said Reynolds, who took severe criticism and made headlines his freshman year for attending church services rather than high school games.

"My freshman year was when it first happened. I took a lot of criticism. People were trying to set up interviews for it, but I'm not going to set up the interview, there's nothing to talk about. I'm not doing this for a show."

And since Reynolds has stuck to his strict schedule of church services before games, the controversy surrounding his choice has since settled.

"Last year it happened and there's no controversy," he said. "I think once you establish yourself and everybody knows how you are, then the questions back off."

REYNOLDS' ATTITUDE, seemingly cocky to some, is another habit he may have picked up while living in Chicago.

"What you learn in your teenage years, you take on for the rest of your life. So I feel like I'm from Chicago," said Reynolds, who honed his game as a pre-teen and teenager on the courts of the Windy City.

"If you didn't play basketball you weren't going to fit in," said Reynolds.

After five years of living in Northern Virginia, Reynolds moved to Chicago from sixth grade on; returning with a new skill-set and outlook on life, just in time to wow the region.

He's grown up faster than most his age, and he knows it.

"I think I had to. I think I wanted to. I brought what I learned from Chicago here. I'm going to take what I saw from other people and put myself in the gym," said Reynolds, who watched friends waste talent with bad decisions.

Since his freshman season, Reynolds has had free reign on Herndon's gymnasium in part because of Hall's dedication to molding the budding star.

"Ever since my freshman year, he's opened the gym in the morning, opened the gym on Sundays," recounts Reynolds. "That gym is, like, sacred. If I get mad and need to get away, I just go to the gym. I like being by myself. I like working out by myself."

REYNOLDS, WHO will attend Oklahoma University on a full basketball scholarship next season, continues his simple walk through what has become a complex ride all around him — a ride he's refused to become a part of. He's kept it simple and humble. As he continues his run to perhaps become the greatest regional player of all time, and the doubters become harder to find, Reynolds has only one warning.

Or perhaps it's a request. After all, it's the doubt that has fueled him.

"If you say I'm not going to do something, I'm going to make sure with all my power that I'm going to do it."

No comments:

Post a Comment